The California Condor Recovery Program has defied the odds to rescue from oblivion the last of the prehistorics and icon of Native Californian cosmology. Threats such as lead ammunition, micro-trash, and sprawling land development threaten these impressive gains of an endangered species. The film “The Condor’s Shadow” documents this struggle.

An Endangered Species Success Story: Flying Free Again, From Baja to Big Sur

The name Chinigchinich, whose habitation is above, means “All-powerful” or “Almighty.” When dancing enrobed in a dress composed of feathers, a crown of the same upon his head, his face painted black and red, he is also known as Tobet. They say that once, while dancing in this costume, he was taken up into heaven, where are located the stars. — Father Friar Gerónimo Boscana, 1846, on the customs of the Acjachemen People of Alta California

During the Pleistocene Era, California condors ranged from what is now British Columbia, down to Baja California Sur, and through much of North America. By 1940, the condor’s range was reduced to a horseshoe-shaped mountain range in southern California.

The almost-10-foot wing-span vulture, the last of the prehistorics, known to soar on thermals up to 140 miles per day scavenging carcasses, had lost its way. Development of railroads and roads, and their attendant Euro-centric population explosion, brought about extinction of roving herds where the deer and the antelope once played. Lead bullets, powerlines, poisoned varmints, microtrash, and target-hungry hunters contributed to the death spiral. With the open range fenced and bulldozed into housing subdivisions, most considered the condor on his last wing.

On April 19, 1987, the final free-flying California condor was captured from the wild and placed in captivity. At that time, only 27 condors remained near-extinction, all in zoos. In the last thirty years, the multi-entity captive breeding and reintroduction effort of the US Fish and Wildlife Condor Recovery Program has brought the Gymnogyps californianus back from the abyss. Even though the population has rebounded to more than 360 birds, flying high in California, Arizona and Baja California, condors still face tremendous challenges. Many wonder whether this endangered species triumph is worth more than $5 million in annual costs, or roughly $13,000 per bird.

Ultimately, experts seek to attain three distinct populations — one wild in California, another wild in Arizona, with a third raised in captivity. Each would have 150 birds and at least 15 breeding pairs. Meanwhile, lead poisoning from hunter’s ammunition persists, wildfires consume habitat, micro-trash ingestion can prove fatal, West Nile Virus threatens fledglings, and it is unknown whether the remaining wildlands can produce sufficient carrion. Furthermore, large-scale land development such as Tejon Ranch and Newhall Ranch threaten to consume habitat, and hunters resist further long-term legislation banning lead ammo. Yet for the first time in decades, the recovery program managers as well as the community at large are optimistic for success.

[vimeo clip_id="114085243" width=600 height=338 ]

Following the Southern California recovery team into wild condor nests, The Condor’s Shadow, the documentary by Jeff McLoughlin, reveals the inherent beauty of these huge birds soaring over the rugged refuges they call home. The film profiles the ongoing challenge of bringing the iconic California condor back from the brink of extinction.

The most celebrated of all their feasts, and which was observed yearly, was the one they called the “Panes,” signifying a bird feast. Particular adoration was observed by them, for a bird resembling much in appearance the common buzzard, or vulture, but of larger dimensions. — Father Friar Gerónimo Boscana

Hol-hol, the Condor-Impersonator, Holds Up the Sky

The condor played a prominent role in the cosmological beliefs and practices of the native people of the Californias. Hence, the bird’s resurgence at the hand of humans can be interpreted as a symbol of hope for renewal of an earth battered by overpopulation, contamination and misuse.

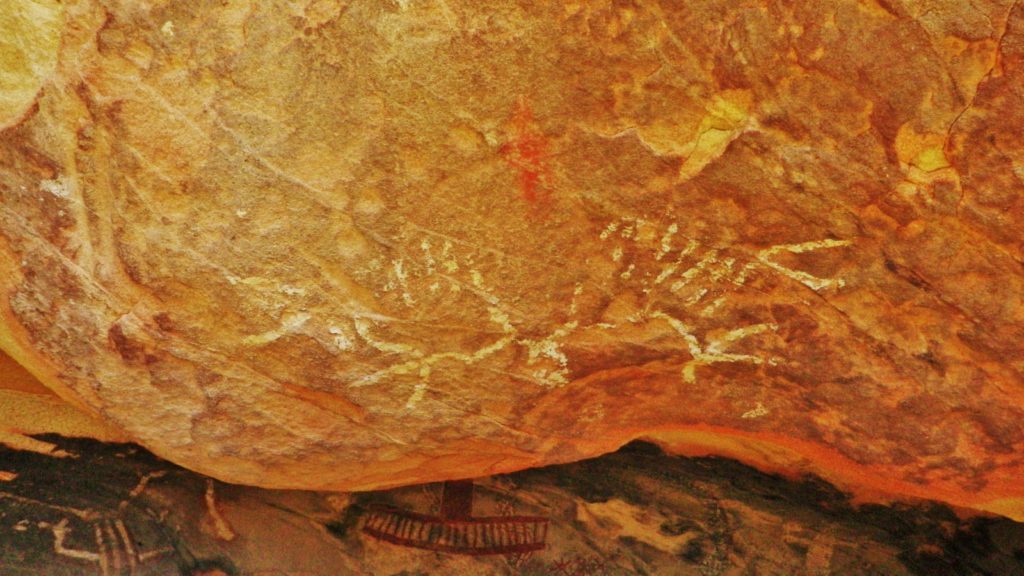

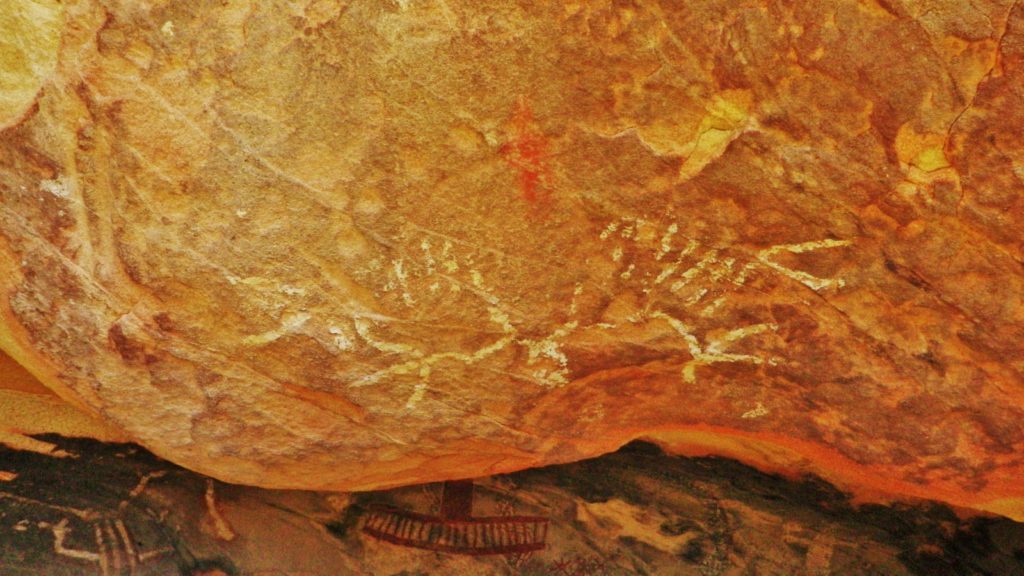

John W. Foster, the Senior State Archaeologist for California, wrote that ritual use of condors has been evidenced through much of historical native California, including widespread sacrifice. In general, this served to transfer the power of the bird sacrificed to those engaged in its ritual killing. Possibly the condor’s association with the dead (being a carrion eater), led to its incorporation into mourning activities and renewal ceremonies.

Not practiced since the time of the missions, first recorded verbal accounts of California condor ceremonies comes from October 8, 1769 when Fr. Juan Crespi observed a large stuffed condor in an Ohlone village near the present day Watsonville.

Many ceremonies throughout California involved dancers dressed in capes of condor skins or condor feather bands. The oldest extant example was collected by the Russian Illya Voznesenski in central California. It is preserved in the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography in St. Petersburg. The condor ceremony took many forms. Central Miwok shamen acquired powers from condors that allowed them to suck supernatural poisons from their patients. Among the Maidu, condor capes were used by Moki or Kuksuyu dancers. These capes were sometimes combined with Golden Eagle feathers to exaggerate the wearer’s height.

The Indians state that said “Panes” was once a female, who ran off and retired to the mountains, when accidentally meeting with “Chinigchinich,” he changed her into a bird, and their belief is, that notwithstanding they sacrificed it every year, she became again animated, and returned to her home among the mountains. — Father Friar Gerónimo Boscana

Perhaps the most detailed description of condor ceremony in southern California comes from the Panes (or bird) festival of the Juaneño (Acjachemen) and Luiseño. It was described by Friar Boscana of Mission San Juan Capistrano and by Friar Peyri of Mission San Luis Rey in the early 19th century. Similar ceremonies were held by the Gabrieleño, Cahuilla, Kumeyaay and Cupeño (Kroeber 1907; 2002).

The Panes (clearly a California condor from its description) is brought to the festival and placed upon an altar constructed for the purpose. The bird had been captured as a nestling, with condor nest sites being owned by the village. It was raised with great care until fully grown and selected for the sacrifice. Slowly, along with much crying and grimaces, the captive birds are killed by strangulation or pressing the heart. The bird’s skin was removed in one piece and the flesh thrown on a fire. Skins and feathers were used to decorate venerated objects for the annual mourning ceremony. California condor skins were also used to make skirts that were retained as important ritual objects by their native owners (Bates et.al. 1993:41; Bates 1982).

California condors could infuse humans with special powers. Vultures and condors, with their keen eyesight, were considered expert at finding lost objects. Among the Western Mono and Yokuts tribes, “money finders” wore full-length cloaks of condor feathers that reputedly enabled them to find lost valuables (Snyder and Snyder 2000:38). This power was extended to finding missing persons among condor shaman of the Chumash.

California condors also played a part in cosmic events. Among the Chumash, condors or eagles were sacrificed based on which celestial body was prominently visible at the time of the ceremony. Eagles were selected for rituals concerned with the Evening Star (Venus), while condors were chosen for rituals associated with the planet Mars (Hudson and Underhay 1978:88; Simons 1983).

References

Bates, Craig T. 1982 “A Historical View of Southern Sierra Miwok Dance and Ceremony.” Ms. on file at California State Department of Parks and Recreation, Sacramento.

Bates, Craig T., Janet M. Hamber and Martha J. Lee 1993 “The California Condor and the California Indians.” American Indian Art 19 (1): 40-48.

Boscana, Geronimo

1846 Chinigchinich: A Historical Account of the Origin, Customs, and Traditions of the Indians at the Mission San Juan Capistrano, Alta California. Translated by Alfred Robinson. New York: Wiley and Putnam.

John W. Foster

Senior State Archaeologist, “Wings of the Spirit: The Place of the California Condor Among Native Peoples of the Californias.” California State Parks.

Hudson, Travis and Ernest Underhay

1978 Crystals in the Sky: An Intellectual Odyssey Involving Chumash Astronomy, Cosmology and Rock Art.

Ballena Press and the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History Cooperative Publication. Santa Barbara, California.

Kroeber, Alfred L.

1907 Indian Myths of South Central California. University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology 4 (4). p. 220.

Snyder, Noel and Helen Snyder

2000 The California Condor: A Saga of Natural History and Conservation. San Francisco: Academic Press.

Pingback: Mass Species Extinction and Wilding Wilderness | WilderUtopia.com

Cermonies began in Canada in the 1990 s by the Native GrandMothers and Female Sagas, to activate the Spirit of the Mother to let her know we are aware and ready for her arairvl. The Condor and Eagle is used as metaphore representing the divided nations. The Nation of the Eagle which represents money and corruption and sheer ignorance of the earth (the masculine, xy), are totally lost in soul for without heart, intuition and the mystical (the feminine, xxy) all is lost, now ,and in the afterlife. Back in 1992 when I was part of the ceremony for The Condor and The Eagle, The Grandmothers had taken back the Drum from the Native Man, as it belonged originally to the GrandMothers to awaken the earth and summon her spirits. The Abuse of the Drum in Mans hands hasnt changed much since then, nothing really has changed other than Native Women still walk behind Native Men. This is out of order and now is the time to have the GrandMothers and all of women walking infront of the Male Shamans and Chiefs, the attention must go back to Woman for once you accept this ,your bloods memory will flood you with Truth, the Mothers truth. We must witness this shift in order to impress the brain. It is logical and mystical once the alignment happens that the children of the New World will have the Condor and Eagle vibration of heart connecting to brain, Intuition connecting to the rational, and the mystical connecting to the material. I anxiously await the New Worlds children for they are the new souls that know theyre purpose. Its time we start listening to the Children instead of the GrandFathers and Male Shamans, these children need the memory of Mother coming from GrandMothers and Female Sagas, this is what needs to be understood in order for any change to take place ,as ,it is The Mother coming back and Not The Father,,,so boys step aside and let the women do what they know best, and in no way do I mean to disrespect man, only to ask him to let the Mother sit infront instead of them O MAMMA