Fritz Lang’s Metropolis hallucinates a futuristic city, a paradise of glass and steel, where underground workers toil endlessly at the giant machines that run the world above. Controlled by the autocratic industrialist, his spoilt son falls for the working class prophet who envisions some mediation between workers and managers. Noted science fiction author H. G. Wells reviews the controversial 1927 German expressionistic masterpiece, directed by Fritz Lang and written by his wife Thea Von Harbou.

Expressionist Utopian Cinema: Fritz Lang’s Metropolis and the Fascism of Industrial Modernity

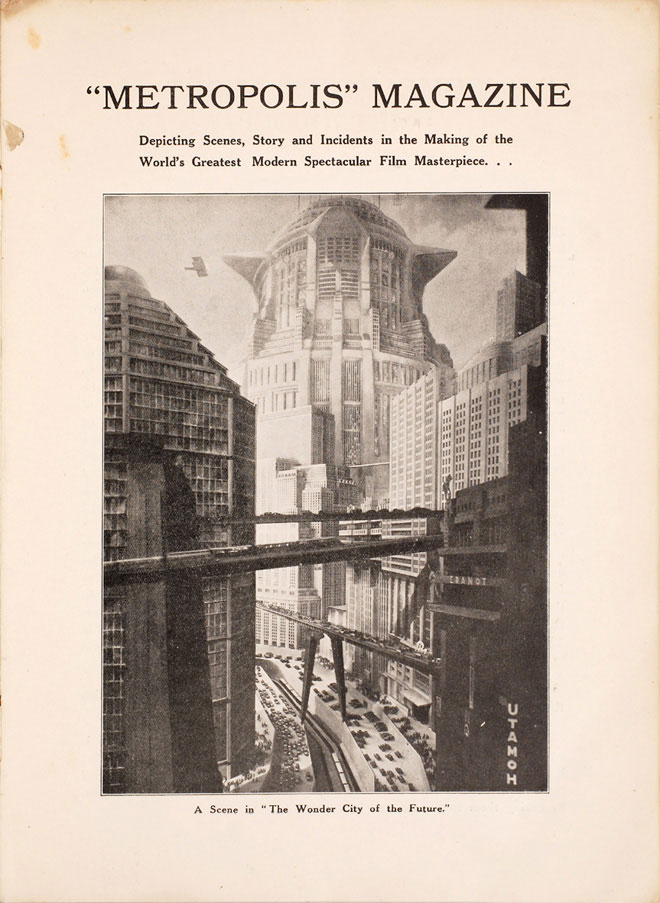

The film tells the story of a futuristic city, with magnificent skyscrapers traversed by biplanes and monorails, with beautiful gardens and sports stadiums. Yet this paradise of glass and steel is not for everyone. Hidden in the bowels of the city we see an image of hell, where workers toil endlessly at the giant machines that run the world above. The city is controlled by the autocratic industrialist Joh Fredersen (Alfred Abel). As he works from his office in the New Tower of Babel, his spoilt son, Freder (Gustav Fröhlich), lives like a child in the city’s Eternal Gardens. But Freder is interrupted from this dream when the beautiful Maria (Brigitte Helm) ascends into the garden in a lift from the depths and becomes smitten with her. So Freder descends to the city of the workers to see the misery in which they live and to work with Maria to bring peace between workers and managers.

Watch this video on YouTube

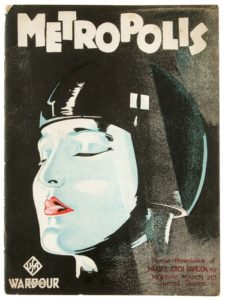

“Metropolis,” Fritz Lang, 1927.

According to Anton Kaes, the film illustrated the modern times of the Weimar period in Germany, reflecting on the rebellious Expressionist avant-garde with a nod to the coming submission under a fascist leader. Metropolis’ “artistic and social context displays the modernist dimension in fascism and the fascist dimension in modernism; it creates a site where modernism clashes with modernity.”

H.G. Wells wrote a review for the New York Times, published on April 17, 1927. Wells didn’t like it much, perhaps because he believed it was “plagiarized” from his 1898 dystopian novel, When The Sleeper Wakes.

__________________

I have recently seen the silliest film. I do not believe it would be possible to make one sillier. And as this film sets out to display the way the world is going. I think [my book] The Way the World is Going may very well concern itself with this film. It is called Metropolis, it comes from the great UFA studios in Germany, and the public is given to understand that it has been produced at enormous cost.

It gives in one eddying concentration almost every possible foolishness, cliché, platitude, and muddlement about mechanical progress and progress in general served up with a sauce of sentimentality that is all its own.

STORY: Film: Carlos Reygadas Meditates on the Mennonites of Mexico

From Roger Ebert: Fritz Lang’s “Metropolis” is hallucinatory–a nightmare without the reassurance of a steadying story line. Few films have ever been more visually exhilarating. Generally considered the first great science-fiction film, “Metropolis” (1926) fixed for the rest of the century the image of a futuristic city as a hell of scientific progress and human despair. From this film, in various ways, descended not only “Dark City” but “Blade Runner,” “The Fifth Element,” “Alphaville,” “Escape from L.A.,” “Gattaca,” and Batman’s Gotham City. The laboratory of its evil genius, Rotwang, created the visual look of mad scientists for decades to come, especially after it was mirrored in “Bride of Frankenstein” (1935). And the device of the “false Maria,” the robot who looks like a human being, inspired the “Replicants” of “Blade Runner.” Even Rotwang’s artificial hand was given homage in “Dr. Strangelove.”

Possibly I dislike this soupy whirlpool none the less because I find decaying fragments of my own juvenile work of thirty years ago, The Sleeper Awakes, floating about in it.

Capek’s Robots have been lifted without apology, and that soulless mechanical monster of Mary Shelley’s, who has fathered so many German inventions, breeds once more in this confusion.

Originality there is none. Independent thought, none.

STORY: Communal Utopia: The Farm in Rural Tennessee

Metropolis: A Utopian Vision of Modernist Architectural Brilliance

Where nobody has imagined for them the authors have simply fallen back on contemporary things. The aeroplanes that wander about above the great city show no advance on contemporary types, though all that stuff could have been livened up immensely with a few helicopters and vertical or unexpected movements. The motor cars are 1926 models or earlier. I do not think there is a single new idea, a single instance of artistic creation or even intelligent anticipation, from first to last in the whole pretentious stew; I may have missed some point of novelty, but I doubt it; and this, though it must bore the intelligent man in the audience, makes the film all the more convenient as a gauge of the circle of ideas, the mentality, from which it has proceeded.

From Anton Kaes: Metropolis offers a hallucinatory vision of the relationship between humanity and machine. The gigantic turbine that dominates the machine room transforms itself before the horrified eyes of Freder into the gaping jaws of a monster, identified in a title card as the biblical god Moloch. Taking the visual motif of the man-eating machine from the famous 1914 Italian film Cabiria, the film uses superimposition to make the machine take on the features of a fuming god. This sudden metamorphosis reveals Metropolis’s underlying ideology, which associates machines with man-eating monsters and the inventor Rotwang with black magic.

The word Metropolis, says the advertisement in English, ‘is in itself symbolic of greatness’- which only shows us how wise it is to consult a dictionary before making assertions about the meaning of words.

Probably it was the adapter who made that shot. The German ‘Neubabelsburg’ was better, and could have been rendered ‘New Babel’. It is a city, we are told, of ‘about one hundred years hence.’ It is represented as being enormously high; and all the air and happiness are above and the workers live, as the servile toilers in the blue uniform in The Sleeper Awakes lived, down, down, down below.

Now far away in the dear old 1897 it may have been excusable to symbolize social relations in this way, but that was thirty years ago, and a lot of thinking and some experience intervene.

That vertical city of the future we know now is, to put it mildly, highly improbable. Even in New York and Chicago, where the pressure on the central sites is exceptionally great, it is only the central office and entertainment region that soars and excavates. And the same centripetal pressure that leads to the utmost exploitation of site values at the centre leads also to the driving out of industrialism and labour from the population center to cheaper areas, and of residential life to more open and airy surroundings. That was all discussed and written about before 1900. Somewhere about 1930 the geniuses of UFA studios will come up to a book of Anticipations which was written more than a quarter of a century ago. The British census returns of 1901 proved clearly that city populations were becoming centrifugal, and that every increase in horizontal traffic facilities produced a further distribution. This vertical social stratification is stale old stuff. So far from being ‘a hundred years hence,’ Metropolis, in its forms and shapes, is already, as a possibility, a third of a century out of date.

But its form is the least part of its staleness. This great city is supposed to be evoked by a single dominating personality. The English version calls him John Masterman, so that there may be no mistake about his quality. Very unwisely he has called his son Eric, instead of sticking to good hard John, and so relaxed the strain. He works with an inventor, one Rotwang, and they make machines. There are a certain number of other people, and the ‘sons of the rich’ are seen disporting themselves, with underclad ladies in a sort of joy conservatory, rather like the ‘winter garden’ of an enterprising 1890 hotel during an orgy. The rest of the population is in a state of abject slavery, working in ‘shifts’ of ten hours in some mysteriously divided twenty-four hours, and with no money to spend or property or freedom. The machines make wealth. How, is not stated. We are shown rows of motor cars all exactly alike; but the workers cannot own these, and no ‘sons of the rich’ would. Even the middle classes nowadays want a car with personality. Probably Masterman makes these cars in endless series to amuse himself.

STORY: Pruitt Igoe Myth: The Death of 20th Century US City

Watch this video on YouTube

Metropolis (1927) – Fritz Lang – Excerpt from Restored Film – The New Pollutants Re-score

Fritz Lang’s Dystopian Vision of Industrial Fascism

One is asked to believe that these machines are engaged quite furiously in the mass production of nothing that is ever used, and that Masterman grows richer and richer in the process. This is the essential nonsense of it all. Unless the mass of the population has the spending power there is no possibility of wealth in a mechanical civilization. A vast, penniless slave population may be necessary for wealth where there are no mass production machines, but it is preposterous with mass production machines. You find such a real proletariat in China still; it existed in the great cities of the ancient world; but you do not find it in America, which has gone furthest in the direction of mechanical industry, and there is no grain of reason in supposing it will exist in the future.

STORY: Orson Welles: Tragic Hero, Sacred Monster, Profane Clown

From Patrick Ward in the “Socialist Review”: But Metropolis has serious flaws. Its central message is that the mediator between workers and bosses – or hands and minds – must be the heart. This leads to a nonsensical plot whereby Freder becomes this “mediator”, the only person capable of healing class antagonisms. The moral is not only against the greed of the rulers, but against workers being led into mindless revolution.

Thea von Harbou, Lang’s wife with whom he wrote the script, went on to become a leading Nazi, and Metropolis won high praise from Joseph Goebbels. Lang fled Germany and subsequently explained his own dissatisfaction with Metropolis: “I was not so politically minded in those days as I am now. You cannot make a social-conscious picture in which you say that the intermediary between the hand and the brain is the heart. I mean, that’s a fairy tale.”

Masterman’s watchword is ‘Efficiency,’ and you are given to understand it is a very dreadful word, and the contrivers of this idiotic spectacle are so hopelessly ignorant of all the work that has been done upon industrial efficiency that they represent him as working his machine-minders to the point of exhaustion, so that they faint and machines explode and people are scalded to death. You get machine-minders in torment turning levers in response to signals – work that could be done far more effectively by automata. Much stress is laid on the fact that the workers are spiritless, hopeless drudges, working reluctantly and mechanically. But a mechanical civilization has no use for mere drudges; the more efficient its machinery the less need there is for the quasi-mechanical minder. It is the inefficient factory that needs slaves; the ill-organized mine that kills men. The hopeless drudge stage of human labour lies behind us. With a sort of malignant stupidity this film contradicts these facts.

The current tendency of economic life is to oust the mere drudge altogether, to replace much highly skilled manual work by exquisite machinery in skilled hands, and to increase the relative proportion of semi-skilled, moderately versatile and fairly comfortable workers. It may indeed create temporary masses of unemployed, and in The Sleeper Awakes there was a mass of unemployed people under the hatches. That was written in 1897, when the possibility of restraining the growth of large masses of population had scarcely dawned on the world. It was reasonable then to anticipate an embarrassing underworld of under-productive people. We did not know what to do with the abyss. But there is no excuse for that today. And what this film anticipates is not unemployment, but drudge employment, which is precisely what is passing away. Its fabricators have not even realized that the machine ousts the drudge.

‘Efficiency’ means large-scale productions, machinery as fully developed as possible, and high wages. The British Government delegation sent to study success in America has reported unanimously to that effect. The increasingly efficient industrialism of America has so little need of drudges that it has set up the severest barriers against the flooding of the United States by drudge immigration. ‘Ufa’ knows nothing of such facts.

Sources:

Anton Kaes: City, Cinema, Modernity

Updated 24 February 2021

Pingback: About Metropolis : SOCKS

Pingback: Orwell's Dystopian Vision Happening Now | WilderUtopia.com

Pingback: 1.10.2017 Doc of the Day | Daily Links & News

Pingback: Virginia Wagner’s ‘Metropolis’ to Open at Kate Oh Gallery – GothamToGo

Pingback: Virginia Wagner’s ‘Metropolis’ to Open at Kate Oh Gallery – GothamToGo

Pingback: Sustainable Vertical Urbanism: The Future of Cities?

Pingback: Appropriating the Media Barrage with Negativland - WilderUtopia