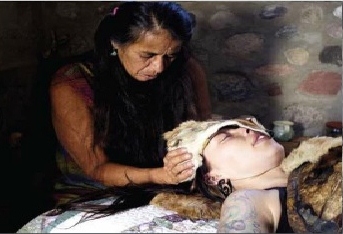

To honor the soul transition of Chumash teacher and healer Cecilia Garcia, we share an article written by her and USC Professor Jim Adams on mind, body and spirit healing.

Strong Spirit of Tradition with Laughter

By Cecilia Garcia, Chumash Medicine Woman, and James Adams, USC Professor of Pharmacology, from Healing With Medicinal Plants of the West, Abedus Press

Renowned Chumash medicine woman Cecilia Garcia departed our human-bond in Ensenada in 2012. A terrible loss, considering her tireless teaching of healing through native plants, ceremony, and laughter for the many-too-many overly-serious and botanically-ignorant migrants to her ancestral South-Central California home.

I had the pleasure of studying with Cecilia twice, once in 2006 at a native plant workshop in La Crescenta and in 2011 at Quail Springs Permaculture Farm in the Cuyama Valley. Both times, USC Professor of Pharmacology Jim Adams accompanied her, adding scientific heft to her inspiring and often raucous sensibilities. They published an excellent guide: Healing with Medicinal Plants of the West, from Abedus Press.

I wrote about the Quail Springs experience in October 2012 here at WilderUtopia.

Following are excerpts from Spirit, Mind and Body in Chumash Healing by Cecilia Garcia and James Adams that capture the spiritual kick in the back-side that was Cecilia, healing through prayer, initiation rites, rock art and community…

The Spirit, Mind and Body

In the olden days, Chumash saw the spirit, mind and body as inseparable entities that could not be treated separately in disease. All healing involved the spirit, the mind and the body. The first steps in healing were more spiritual, which opens the mind and body to healing. The next steps in healing may have been directed more to the mind and body. In current society, the body and mind are usually treated separately. Diseases are considered to be the result of a problem with one component of the body. For instance, heart disease is considered a problem of high blood pressure leading to a weak heart, or atherosclerosis leading to thrombi that damage the heart. Drugs are administered to control high blood pressure or to control cholesterol in order to prevent atherosclerosis and thrombosis. There is usually only a very ineffective attempt to control weight that would prevent or ameliorate heart disease.

In the Chumash village, the approach was very different. Prevention of disease was the most important job of the medicine people. Obesity was not tolerated, except perhaps among some chiefs (wot in Chumash, pronounced wote). Obesity was considered a sign of laziness, an attitude that was not tolerated in a Chumash village (1). Everyone in the village had to work together to make the village survive. Everyone knew their job and knew they were critical to the survival of the village.

Chumash lived along the California coast from Malibu to San Luis Obispo and inland ~50 miles or more. Chumash people built the Missions at Ventura, Santa Barbara, Santa Ynez, La Purisima and San Luis Obispo. They spoke the Chumash language, a Hokan language, of which there were many dialects. Chumash people currently reside throughout Southern California, and elsewhere. There is one small Chumash reservation at Santa Ynez.

Prayer in Healing

In the Chumash village, all healing started with prayer. Prayer invites God (Xoy in Chumash, pronounced Hoy) to participate in the healing process. Prayer came in many forms and could be as simple as the patient and healer praying together. Prayer sometimes involved smudging with white sage (Salvia apiana) (3). The healer, or an elder from the village, put a small branch of dried white sage in a suitable container such as a seashell, typically an abalone shell. The white sage was ignited with fire. The flames were blown out allowing the white sage to smolder and smoke. The smoke from white sage has a pleasant smell and is thought to help carry prayers to God (1). The healer prayed for the health of the patient while moving the seashell to allow the smoke to touch every part of the patient’s body including the soles of the feet. The healer sometimes touched the patient’s back with an eagle or hawk wing to draw out harmful spirits (nunasus). The wing was then flicked down to send the harmful spirits back into the underworld where they originated (4). Smudging with white sage is still practiced by Chumash people today.

STORY: Chumash Story: Seeds of Creation and the Rainbow Bridge

‘When you burn white sage, you have to pray. You’re supposed to be healing someone. You’re supposed to be at attention, because white sage is our protection. If you’re not praying, someone is not being protected.’ Cecilia Garcia (3).

Prayer is now almost completely gone from hospitals and clinics. It may be appropriate to learn from Chumash practices and bring prayer back into hospitals and clinics. Prayer is free, comforts patients and may even decrease mortality in cardiac patients (5). Prayer is completely safe for patients in hospitals as demonstrated by numerous clinical trials (6). Since prayer has been shown to be safe for patients, prayer is not dangerous to the practice of medicine.

The Initiation Ceremony

When a boy became 8 years old it was time for him to begin the process of becoming a man (1). An initiation ceremony took place, usually involving several boys. The purpose of the ceremony was to assess the fitness of a boy and to prepare him for manhood by having him pass through a major challenge. The elders and the Healers, ‘antap in Chumash (pronounced gontop), of the village decided when the time was right for this to occur. Sometimes teenage girls also went through this ordeal. The ‘antap prepared a decoction of Datura wrightii, called momoy in Chumash. This plant is also called California jimson weed, toloache or thorn apple and was formerly named Datura meteloides. The stems and roots of the plant were used. Typically ~0.25 Kg of the plant was used for every liter of water. The preparation was placed in water tight baskets and allowed to ferment in the sun for several days. The decoction develops a light brown color when it is ready. A few white sage leaves, S. apiana, were added in the final day of fermentation of the momoy. White sage was thought to enhance any medicine, since white sage purifies the mind and spirit. When the time was right, the momoy preparation was taken to the mother of an 8-year-old boy. She was instructed to have her son drink the momoy preparation (1).

STORY: Chumash Sky and Earth Deities and Cosmological Rock Art

Momoy stems and leaves contain atropine and scopolamine as well as apohyoscine, norhyoscine, meteloidine and norhyoscyamine (7). The roots contain these compounds and (-)-3?,6?-ditigloyloxytropane, 3,6-ditigloyloxytropan-7-ol, tropine, pseudotropine and 3,6-dihdroxytropane (7). Atropine and scopolamine have similar pharmacology and cause dry mouth, blurred vision, visual and auditory hallucinations, respiratory depression and death. The pharmacology of the other compounds has not been reported. Scopolamine is erratically and slowly absorbed into the brain, taking up to 13 h to be absorbed.

Momoy is currently abused in the American Southwest and results in many deaths and hospitalizations every year. Unfortunately, the Internet, popular fictional accounts and word of mouth have spread rumors that eating the seeds is safer than using the rest of the plant, since the seeds are supposed to contain less atropine and scopolamine. This appears to be completely false. Eating 20 or more seeds has resulted in many deaths (8). There are three common types of deaths that occur from eating momoy (9). The first occurs when the person panics as the auditory and visual hallucinations start. The person may drive a car into a fatal accident or have some other fatal accident, usually due to loss of vision. The second type of death occurs when a person on momoy has had a nonfatal accident and goes to the emergency room. The doctors in the emergency room may anesthetize the person. This is usually fatal since anesthesia causes respiratory depression that is additive with the respiratory depression caused by momoy. The third type of death occurs in people who have very slow and erratic absorption of scopolamine. Perhaps one quarter or so of people are in this category. These people take more momoy when the first dose has no effect. Death occurs from D. wrightii ingestion with blood levels of as much as 47 ng ml?1 of atropine and 21 ng ml?1 of scopolamine. Urine levels at death can be as high as 200 ng ml?1 of atropine and 95 ng ml?1 of scopolamine (3). Death from respiratory depression may occur as late as 13 h after the initial ingestion of momoy.

Red Harvester Ants

Some boys were initiated with red harvester ants, rather than momoy (3). Red harvester ants (Pogonomyrmex californicus, shutulhul in Chumash, pronounced shuetulhul) were once abundant in California, but are being replaced by small, aggressive Argentine ants that were introduced into California several years ago. Red harvester ants were used as a cure for diarrhea of all kinds (3). They were also used to induce sacred dreams, hallucinations for the initiation of boys into manhood. They were considered safer than momoy. The ants were administered by an ant doctor, usually a woman, who scooped the ants up on eagle down. She would then pop the live ants and eagle down into the mouth of the boy, who was instructed to swallow everything. Of course, the ants stung the inside of the mouth and throat as they were swallowed. The venom of red ants contains formic acid and polypeptide kinins that induce pain, inflammation and can lower blood pressure (3). Some kinins have nicotinic cholinergic activity that may be responsible for the induction of hallucinations. About 250 or more ants were required for this process. Fortunately, the abuse of ants as hallucinogens is minimal in our present society. There is no evidence of anyone using ants. There are no reports of contemporary harvester ant use in California. The safety or dangers of this process are not reported.

Pictographs as Healing Images

Southern California is privileged to have many sites where Chumash pictographs occur. Many of these pictographs are beautiful pieces of art. They were typically painted in black, red and white. Sometimes yellow, green, orange and blue can be found in pictographs. Unfortunately, these pictographs are not being protected in most of the sites. Some of the most beautiful pictographs are already gone forever. Fortunately, many of the pictographs have been published as drawings (10).

The primary use of pictographs was as healing images. This is what Cecilia Garcia’s grandparents taught her when they instructed her in Chumash healing practices. Typically the ‘antap painted pictographs in a cave near a stream. Patients would come to the cave to be healed. Sometimes they came from long distances, such as Chemehuevi people who came to Chumash pictograph sites nearly 100 miles away.

A visitor to a pictograph site would sit or lie in the cave and gaze at the rock art during the healing procedure. The purpose of the pictographs was to relax or even amuse patients and help take their minds off their problems. This type of relaxation therapy is well known to help in healing processes (11). Another use of the pictographs was to explain the human body. For instance a woman having trouble conceiving may have been shown a pictograph depicting the uterus. The ‘antap may have explained that the uterus was important in conception and pregnancy. The purpose of the pictograph of the uterus was to show the woman, and her husband, a part of her body that could not otherwise be seen. This is commonly done in doctor’s offices today. Phallic symbols may have served the purpose of encouraging conception, much as the uterus symbol. Cupules are frequently found in Chumash areas. Cupules are pits pecked into the rock. Powder from pecking the cupules was used by Pomo and perhaps also Chumash, in fertility ceremonies for a woman and her husband (1). The powder from the cupules was inserted into the wife by the husband prior to intercourse.

Another type of pictograph was used to tell a story. The most famous story pictograph is now almost entirely lost. It shows sky coyote, Snilemun in Chumash (pronounced shneelaymune). Snilemun is seen in the sky as the north star. Snilemun plays peon (pronounced payoan) with the sun. Peon is a gambling game where one player hides a stick in one of his hands. The other player must guess which hand holds the stick. Every year, Snilemun and the sun play peon. If the sun wins, it will be a very hot year and many people will die. The sun takes his winnings in human lives. If coyote wins, it will be a wet year and people will survive. Peon is played continuously for many days. Coyote uses ephedra to stay awake at night during the game.

STORY: Chumash Legend: Hole in the Blanket

Unfortunately, there is substantial misinformation about Chumash pictographs. One writer claimed that the pictographs were painted while the ‘antap was under the influence of momoy (12). This is impossible since momoy blurs the vision so much, that no one could paint a pictograph under the influence of momoy. There is a legend that an ‘antap painted a pictograph that showed people with blood coming out of their mouths, reminiscent of tuberculosis (1). This pictograph may have been painted to warn other Chumash not to abandon their traditional ways, and stay away from the Missions, or they would die.

The painted cave near Santa Barbara (below) was considered taboo by some Chumash because they thought the pictographs were depictions of death (1). There is a story of a man who went to a pictograph site (shrine) to pray for his daughter to get well. When the daughter died, he returned to the site and destroyed the pictographs (1). Apparently, in the olden days, some people assumed the ‘antap had power over life and death, called ‘ayip (a powerful supernatural medicine, pronounced ghiyeep). The authors are not aware of any study that has ever shown that anyone has the power to make another sick or die from a distance.

Some writers have stated that the Chumash people did not dare to approach pictograph sites (12,13). The pictographs have been explained as attempts to ‘placate an inimical universe,’ prevent death, drive the Spanish and the Mexicans away, cause drought and famine, and avoid storms (13). It is impossible to know if these claims are true. A rebellion occurred in 1824, where many Chumash took over the Mission at La Purisima and fought the Mexicans. This made it very clear that the Chumash wanted the Mexicans to go away and leave the Missions to the Chumash. It could also be that the pictographs have been over interpreted by some authors.

Some pictographs can be easily interpreted by observers. Other pictographs appear more abstract. The true intent of the ‘antap or artist who painted a pictograph is not known for the majority of pictographs. Pictographs may have had specific meanings or may have been painted as abstractions to relax the observer. As with all art, each observer can form an opinion. It is a shame that observation of these pictographs is becoming more difficult due to restricted entry into pictograph sites. It is also a shame that many of the pictographs are not being protected and are being allowed to fall off the rocks.

The Importance of a Supportive Village

In a Chumash village, every member of the village was essential to the survival of the village. When any member of the village became sick, it was essential to the village for that person to be healed. The ‘antap had to know how to heal sick people and get them back to work for the village. The ‘antap knew how to heal with prayer, plants, heat therapy, healing touch (14) and by comforting.

The ‘antap comforted patients with many techniques including reassurance, nourishment and helping the patient find a new job in the village, if necessary. Children and teenagers were frequently comforted by wrapping them in soft, rabbit furs. Fire was used to warm and comfort the sick (14). A new job would be found, for instance, for a hunter who had lost a leg and could no longer run after deer. The village supported the sick until new positions could be found for them.

Comfort is very important in the healing process. Comfort is largely missing in the current health care system. For instance, women recently diagnosed with breast cancer may become so distraught that they suffer from other conditions. It has been shown that women with phobic anxiety suffer from more coronary heart disease than other women (15). Anxiety is a health hazard.

Today, this supportive environment is gone for many patients. For instance, a patient who lives alone may not be able to switch jobs, as dictated by a medical condition. The patient may have bills to pay that cannot wait for the patient to find another job. A sick patient may quickly lose a job, since there are many other people looking for work.

Conclusions

This work describes the Chumash views of mind and body in healing. There is a large literature base on these subjects in other cultures (16–18). However, some of the writing about American Indians has focused on the unusual aspects of healing. Drug-induced frenzies, shape shifting, removing objects from patients’ bodies without surgery and other such unusual practices are discussed in many publications. The purpose of the current work is to humanize the Chumash practices and underscore the importance of learning Chumash healing practices in modern medicine. This is not a new message, but must be restated in order to overcome the overstated views of some historical figures who found the Chumash to be naked, uncivilized (2) and by implication insignificant with respect to learning.

The Chumash ‘antap treated patients by strengthening their spirits, minds and bodies. This is why the ‘antap were religious leaders and healers. Recent surveys indicate that up to 79% of the American population professes a belief in God (19), 82% of American teenagers believe in God (20) and 60% of American doctors have religious beliefs (21). However, many doctors do not participate in the spiritual health of their patients. Instead, religious leaders are called into the hospital to help with spiritual health. This may leave the patient with the feeling that spiritual health is not important to doctors. Doctors usually only treat the patient’s bodies to cure disease. Occasionally, relaxation therapy may be used to help treat the mind. However, it is more common to use drugs such as benzodiazepines to calm the mind. This drug-induced calming may not solve the problem facing the patient. Psychotherapy can be of benefit, but may not be used by patients. In the Chumash village, the ‘antap practiced a form of psychotherapy that was mandatory in healing. Many people in our current society feel isolated and could benefit from a supportive environment. Women with small social circles, as opposed to large social circles, suffer from more coronary artery disease (22). They may find such supportive environments in churches or clubs. The hospital should also be a supportive environment.

References

Updated 14 November 2021

Pingback: Self-Healing with Chumash Native Plant Medicine | WilderUtopia.com

Pingback: Chumash Healing with Wild Local Plants | Whole Life Times — Los Angeles Holistic Health Magazine

Pingback: Chumash Elder Speaks on Healing Humanity and the Climate - WilderUtopia