The imaginative utopian vision of Italo Calvino in “Invisible Cities” should have inspired the urban planning of China’s cities undergoing rapid industrialization. This essay poses the what-if notion of imaginative urban design that could have overcome some of the problems of crowded, polluted urban mega-cities of 10 million residents or more.

Chinese Urban Utopian Overdose Could Have Learned from Italo Calvino’s “Invisible Cities.”

The rapid industrialization of China includes proliferation of megacities, including Tianjin, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Chongqing, Chengdu and Wuhan. In all, 43 cities have populations of one-million-plus today, with a projected 221 by 2025, a mass migration of millions from the impoverished Chinese countryside, leading to significant urban social and environmental problems.

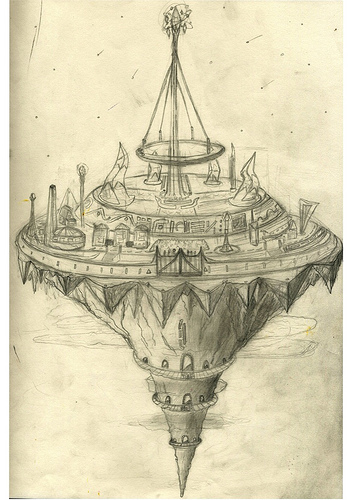

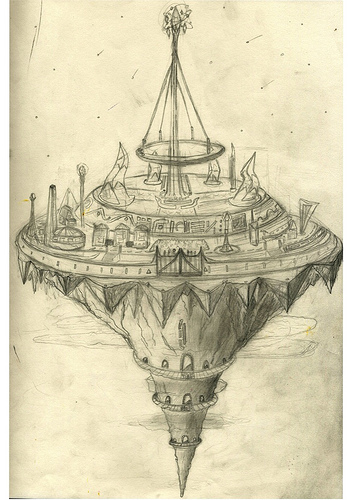

A recent essay in Foreign Policy ponders the issue in light of Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities. In Calvino‘s book, Marco Polo reports to China’s emperor Kublai Khan on the different cities he has visited. In one vignette, he tells about a city named Irene only seen from a distance, but never from inside. People gather at a high plateau to view Irene‘s skyline, imagining how life there could be. No one had even lived there or even visited. No one knew if it even was a city. Trouble happens when humans actually build them from their imagination.

Even the great Khan’s atlas contained maps of the imaginary promised lands: New Atlantis, Utopia, the City of the Sun, Oceana, Tamoé, New Harmony, New Lanark, Icaria. He then pondered the cities that menace in nightmares and maledictions, such as Enoch, Babylon, Yahooland, Butua, Brave New World. He asked Marco Polo how humanity could avoid such nightmares, and the latter responded:

“The inferno of the living is not something that will be; if there is one, it is what is already here, the inferno where we live every day, that we form by being together. There are two ways to escape suffering it. The first is easy for many: accept the inferno and become such a part of it that you can no longer see it. The second is risky and demands constant vigilance and apprehension: seek and learn to recognize who and what, in the midst of inferno, are not inferno, then make them endure, give them space.”

— Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities

Unlivable Cities

By Isaac Stone Fish, from Foreign Policy

Isaac Stone Fish’s essay examines China’s megalopolises, seeming impressive on paper, but they are awful places to live.

In Invisible Cities, the novel by the great Italian writer Italo Calvino, Marco Polo dazzles the emperor of China, Kublai Khan, with 55 stories of cities he has visited, places where “the buildings have spiral staircases encrusted with spiral seashells,” a city of “zigzag” where the inhabitants “are spared the boredom of following the same streets every day,” and another with the option to “sleep, make tools, cook, accumulate gold, disrobe, reign, sell, question oracles.” The trick, it turns out, is that Polo’s Venice is so richly textured and dense that all his stories are about just one city.

A modern European ruler listening to a visitor from China describe the country’s fabled rise would be better served with the opposite approach: As the traveler exits a train station, a woman hawks instant noodles and packaged chicken feet from a dingy metal cart, in front of concrete steps emptying out into a square flanked by ramshackle hotels and massed with peasants sitting on artificial cobblestones and chewing watermelon seeds. The air smells of coal. Then the buildings appear: Boxlike structures, so gray as to appear colorless, line the road. If the city is poor, the Bank of China tower will be made with hideous blue glass; if it’s wealthy, our traveler will marvel at monstrous prestige projects of glass and copper. The station bisects Shanghai Road or Peace Avenue, which then leads to Yat-sen Street, named for the Republic of China’s first president, eventually intersecting with Ancient Building Avenue. Our traveler does not know whether he is in Changsha, Xiamen, or Hefei — he is in the city Calvino describes as so unremarkable that “only the name of the airport changes.” Or, as China’s vice minister of construction, Qiu Baoxing, lamented in 2007, “It’s like a thousand cities having the same appearance.”

When you have forded the river, when you have crossed the mountain pass, you suddenly find before you the city of Moriana, its alabaster gates transparent in the sunlight, its coral columns supporting pediments encrusted with serpentine, its villas all of glass like aquariums where the shadows of dancing girls with silvery scales swim beneath the Medusa-shaped chandeliers. If this is not your first journey, you already know that cities like this have an obverse: you have only to walk a semi-circle and you will come into view of Moriana’s hidden face, an expanse of rusting sheet metal, sack-cloths, planks bristling with spikes, pipes black with soot, piles of tins, behind walls with fading signs, frames of staved-in straw chairs, ropes good only for hanging oneself from a rotten beam. From one part to the other, the city seems to continue, in perspective, multiplying its repertory of images: but instead it has no thickness, it consists only of a face and an obverse, like a sheet of paper, with a figure on either side, which can neither be separated nor look at each other.

— Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities

Why are Chinese cities so monolithic? The answer lies in the country’s fractured history. In the 1930s, China was a failed state: Warlords controlled large swaths of territory, and the Japanese had colonized the northeast. Shanghai was a foreign pleasure den, but life expectancy hovered around 30. Tibetans, Uighurs, and other minorities largely governed themselves. When Mao Zedong unified China in 1949, much of the country was in ruins, and his Communist Party rebuilt it under a unifying theme. Besides promulgating a single language and national laws, they subscribed to the Soviet idea of what a city should be like: wide boulevards, oppressively squat, functional buildings, dormitory-style housing. Cities weren’t conceived of as places to live, but as building blocks needed to build a strong and prosperous nation; in other words, they were constructed for the benefit of the party and the country, not the people.

“…the people who move through the streets are all strangers. At each encounter, they imagine a thousand things about one another; meetings which could take place between them, conversations, surprises, caresses, bites. But no one greets anyone; eyes lock for a second, then dart away, seeking other eyes, never stopping…something runs among them, an exchange of glances like lines that connect one figure with another and draw arrows, stars, triangles, until all combinations are used up in a moment, and other characters come on to the scene… ”

— Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities

Even today, most Chinese cities feel like they were cobbled together from a Soviet-era engineering textbook. China’s fabled post-Mao liberal reforms meant that the country’s cities grew wealthier, but not that much more distinct from each other. Beijing has changed almost beyond recognition since Deng Xiaoping took power in 1978, but to see what Beijing looked like in the past, visit a less developed part of China: Malls in Xian, a regional hub in central China famous for its row upon row of grimacing terracotta warriors, look like the shabby pink structures that used to dot western Beijing.

Yes, China’s cities are booming, but there’s a depressing sameness to what you find in even the newest of new boom-towns. Consider the checklist of “hot” new urban features itemized in a 2007 article in the Communist Party mouthpiece the People’s Daily, including obligatory new “development zones” (sprawling corporate parks set up to attract foreign direct investment), public squares, “villa” developments for the nouveau riche, large overlapping highways, and, of course, a new golf course or two for the bosses. The cookie-cutter approach is such that even someone like Zhou Deci, former director of the Chinese Academy of Urban Planning and Design, told the paper he has difficulty telling Chinese cities apart.

“When a man rides a long time through wild regions he feels the desire for a city. Finally he comes to Isidora, a city where the buildings have spiral staircases encrusted with spiral seashells, where perfect telescopes and violins are made, where the foreigner hesitating between two women always encounters a third, where cockfights degenerate into bloody brawls among the bettors. He was thinking of all these things when he desired a city. Isidora, therefore, is the city of his dreams: with one difference. The dreamed-of city contained him as a young man; he arrives at Isidora in his old age. In the square there is the wall where the old men sit and watch the young go by; he is seated in a row with them. Desires are already memories.” — Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities

This model of endless fractal Beijings wouldn’t be so bad if the city itself were charming, but it is a dreary expanse traversed by unwalkable highways, punctuated by military bases, government offices, and other closed-off spaces, with undrinkable tap water and poisonous air that’s sometimes visible, in yellow or gray. And so are its lesser copies across the country’s 3.7 million square miles, from Urumqi in the far west to Shenyang way up north. For all their economic success, China’s cities, with their lack of civil society, apocalyptic air pollution, snarling traffic, and suffocating state bureaucracy, are still terrible places to live.

What makes Argia different from other cities is that it has earth instead of air. The streets are completely filled with dirt, clay packs the rooms to the ceiling, on every stair another stairway is set in negative, over the roofs of the houses hang layers of rocky terrain like skies with clouds. We do not know if the inhabitants can move about the city, widening the worm tunnels and the crevices where roots twist: the dampness destroys people’s bodies, and they have scant strength; everyone is better off remaining still, prone; anyway, it is dark. From up here, nothing of Argia can be seen; some say, “It’s down below there,” and we can only believe them. The place is deserted. At night, putting your ear to the ground, you can sometimes hear a door slam. — Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities

I spent seven years in China, living there until the end of last year. I’ve visited 21 of China’s 22 provinces and all five of its questionably named “autonomous” regions. In a traffic jam in the central metropolis of Wuhan, a barrage of car horns honking at once nearly made me deaf; smog the color of gargled milk hung over Nanjing the week I spent there, obscuring the city’s old rivers and bridges; at one of the nicest hotels in Tangshan, a city of 3 million famous for its steel industry, its 1976 earthquake, and its cabbage, I opened my window and found myself surrounded by smokestacks. I spent six years in Beijing, two months in Shanghai, a week in Tianjin, and 45 minutes in a cab on the way to the Chongqing airport. But of all the places I’ve been, I’d vote Harbin China’s least livable metropolis, at least during the three winter months I spent there as a student in 2005.

“Yes, the empire is sick, and, what is worse, it is trying to become accustomed to its sores. This is the aim of my explorations: examining the traces of happiness still to be glimpsed, I gauge its short supply. If you want to know how much darkness there is around you, you must sharpen your eyes, peering at the faint lights in the distance.”

— Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities

Chinese central government propaganda has gotten more sophisticated, even believable over the years, but official descriptions of cities are a major exception. Xiamen, for example, a sweltering concrete mess across the strait from Taiwan, is known as the “Garden of the Sea.” Harbin, a gray Manchurian industrial powerhouse 300 miles south of Siberia that McKinsey says will be the world’s 55th-most dynamic city in 2025, gets the award for the worst abuse of language: It is widely known in China as “The Little Paris of the Orient,” even though the two cities have nothing in common besides roads, people, buildings, and a fondness for bread.

Updated 4 March 2023

Pingback: China's Urban Utopia: Ghost Cities and Propaganda Theme Parks | WilderUtopia.com

Pingback: Sustainable Vertical Urbanism: The Future of Cities? | WilderUtopia.com