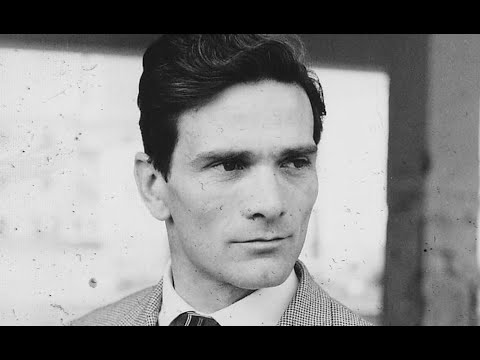

Almost forty years after his violent death, Pier Paolo Pasolini, filmmaker, poet, journalist, novelist, playwright, painter, actor, and all-around intellectual public figure, remains a subject of passionate argument. Best known for a subversive and difficult body of film work, loaded with Renaissance and Baroque iconography, he championed the disinherited and damned of postwar Italy, mingling an intellectual leftism with a fierce Franciscan Catholicism.

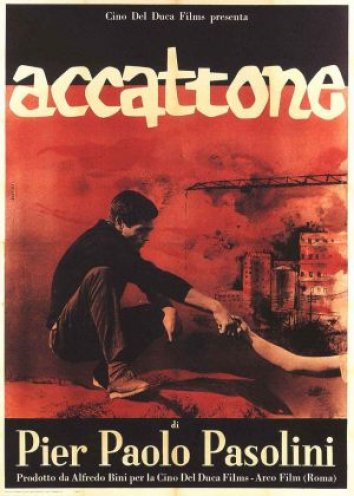

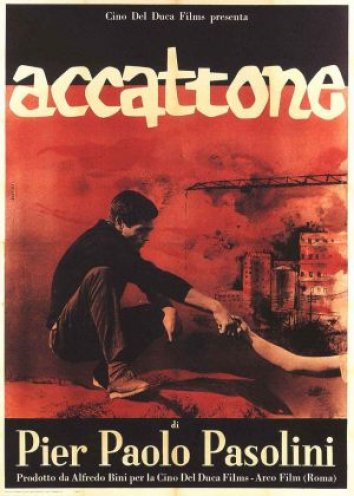

Among his earliest movie jobs was writing additional dialogue for Federico Fellini’s Nights of Cabiria (1957). Soon he was directing his first film, Accattone (1961), a tale of street crime whose style and content greatly influenced the debut feature of his friend Bernardo Bertolucci, La commare secca (1962), for which Pasolini also wrote the original story. The outspoken and always political Pasolini’s films became increasingly scandalous—even, to some minds, blasphemous—from the gritty reimagining of the Christ story The Gospel According to Matthew (1964) to the bawdy medieval tales in his Trilogy of Life (1971–1974).

Tragically, Pasolini was found brutally murdered weeks before the release of his final work, the grotesque, Marquis de Sade–derived Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom (1975), still one of the world’s most controversial films.

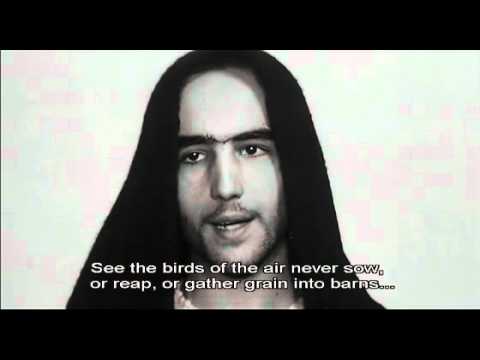

Watch this video on YouTube

Whoever Says the Truth Shall Die. The hour-long Dutch documentary, from 1981, six years after Pasolini’s untimely passing. Directed by Philo Bregstein.

The Life and Death of Pier Paolo Pasolini

By Geoff Andrews, For the complete article, see: Open Democracy

In the early hours of 2 November 1975, the body of Pier Paolo Pasolini – writer, poet, film director and one of Italy’s leading intellectuals – was found on wasteland in Ostia, just outside Rome. Several hours later, Pino “The Frog” Pelosi, a 17-year-old male prostitute, was arrested speeding along the Ostia seafront in Pasolini’s Alfa Romeo. Pelosi was accused of Pasolini’s brutal murder. It was alleged that Pasolini had picked up Pelosi outside Termini train station, taken him to a pizzeria and then driven to Ostia for sex. Pelosi himself claimed that he had killed Pasolini in self-defense after the latter had attempted to sodomize him with a wooden stick, but after a lengthy trial he was found guilty in 1976 and sentenced to nine years in jail.

Many people were unhappy with the murder verdict. The actress Laura Betti, who had appeared in many of Pasolini’s films, organised a campaign for an inquiry into his death. She argued that it had a deeper political significance. After all, Pasolini had made many enemies. In the weeks leading up to his murder he had condemned Italy’s political class for its corruption, for neo-fascist conspiracy and for collusion with the Mafia. In articles for Corriere della Sera he had called for Italy’s political class to be put on trial.

STORY: The Ongoing Reconsideration of Pier Paolo Pasolini

Other friends and supporters of Pasolini, like the film director Bernardo Bertolucci, used the absence of blood on Pelosi’s clothes and the nature of the marks on Pasolini’s body to cast doubt on the notion that Pelosi alone could have committed the murder. Bertolucci, who worked as an assistant on Pasolini’s first film Accattone, spoke of the way Pasolini’s life and public image had been “savaged” in the period leading up to his murder. Pasolini’s last film Salo o le 120 Giornate di Sodom depicted Mussolini’s fascists as sodomites, and he had received death threats from active neo-fascist groups.

The doubts that emerged over responsibility for the killing did not abate after Pelosi’s confession. The trial pathologist, Faustino Durante, suggested that the murder was likely to have been committed by more than one person. The newspaper Paese Sera published a letter from a witness saying that a car containing four people from Catania in Sicily followed Pasolini to Ostia. This material, though submitted, was never used in the trial. These concerns were partially reflected when a court decided in 1977 that Pasolini had been “murdered by Pelosi and persons unknown”; but at the appeal in 1979, this judgment was amended and Pelosi now regarded as the sole murderer.

A Cultural Subversive

The starting-point for any criminal investigation is the underlying motive; who had reason to kill Pier Paolo Pasolini and who benefited from the death? It is impossible to answer these questions without considering Pasolini’s role as a dissident and one of Italy’s most prominent intellectuals.

Pasolini’s work spanned the disciplines of poetry, literature and cinema, while his political commitments were intense, controversial and unpredictable. The recurring theme dominating Pasolini’s life was power. In his work, as in his personal experiences, he encountered power in all its hidden, conspiratorial and censorious forms. More than thirty legal cases were brought against him for blasphemy and obscenity arising from his films and writing. His confrontations with power kept him simultaneously at the margins and the centre of Italian public life. He was a dissident not only from the Italian mainstream but also from the Italian Communist Party (PCI) and the wider left, whose orthodoxies and conventions he often contested.

Watch this video on YouTube

“I don’t believe we will ever again have any form of society in which men will be free. One should not hope for it. One should never hope for anything. Hope is something invented by politicians to keep the electorate happy.” — Pier Paolo Pasolini

Pasolini, born in Bologna in 1922, was brought up in the family home in Casarsa, in Italy’s northeast Friuli province; it was here in 1942 that he produced his first published work, Poems of Casarsa – and collection written in Friulian dialect.

Pasolini’s use of dialect owed much to the influence of Antonio Gramsci, the Sardinia-born Marxist who wrote his major works from Mussolini’s prison cell. Pasolini took from Gramsci the need for a national popular art that would engage a critical working class. This was to be part of a wider political struggle to project an alternative proletarian culture in opposition to ruling-class hegemony and occupied the breadth of Pasolini’s early work, through his poetry and subsequently through his writings and films. His celebrated 1957 poem, The Ashes of Gramsci, reflected his debt to Gramsci’s thought; notably the way “forbidden voices” can inform social change.

Watch this video on YouTube

Teorema (1968), Written and Directed By Pier Paolo Pasolini. An upper-class Milanese family is introduced to, and then abandoned by, a divine force. Two prevalent motifs are the desert and the timelessness of divinity.

His concern with marginal working-class culture was evident in his first novel published in 1954, Ragazzi di Vita (Boys of the Street) which depicted the violent existence of the Roman sub-proletariat and the repressive nature of the state. The raw daily realities of Rome’s young poor in slums like the borgate, apparent to Pasolini from his homosexual encounters, were further portrayed in his second book, Una Vita Violenta (A Violent Life), which won the Premio Crotone in 1959.

Una Vita Violenta formed the basis for Pasolini’s first film, Accattone, made in 1961 in the borgate (slums), in the spirit of the Italian neo-realist tradition (though with some innovations, notably camera focus and lighting). Writing about Accattone in 1975, Pasolini described it as a “laboratory” for understanding a “way of life”: “The peasant culture of the south gave the Roman sub-proletarians not only psychological traits but completely original physical traits as well. It located a real ‘race’.”

He attributed the way of life of the Roman poor to the combination of economic deprivation and the seedy underworld which characterized the repressive 1950s, which Pasolini saw in some ways as a continuity between the fascist era and the subsequent Christian democrat regime. He defined this regime as “clerico-fascism” for its repressive use of the state and its manipulation of power. He argued that this was illustrated in Rome by the marginal existence of the sub-proletariat which was in conflict with a criminal police force. Other social classes had little knowledge of the real conditions of the Roman slums, where different ways of living and value systems were evident.

These ways of living were transformed as the 1960s unfolded, when Italy underwent an economic consumer boom with the new freedoms and aspirations epitomized by films like Fellini’s La Dolce Vita. After Accattone and Mamma Roma (1962), Pasolini lost his earlier optimistic belief that neo-realism and other critical cultural forms could drive radical social change. He despaired at the emergence of a neo-capitalist empire set on destroying popular culture. He no longer believed that Gramsci’s reconciliation between popular culture and political change was possible. For Pasolini, the kind of mass hedonism that emerged during the 1960s shattered his belief in working-class innocence. “My films were not for mass consumption,” he said later. “I could imagine nothing worse than producing something for an alienated mass culture, which I had no sympathy for.”

This shattering realization remained with Pasolini and dominated his remaining work. His films took a new direction and reflected a more complex philosophical commitment, with points of convergence as well as contradiction between his Marxism and Catholicism. Il Vangelo Secondo Matteo (The Gospel According to Matthew) filmed in 1964 in the poor southern town of Matera – amongst the Sassi, the ancient cave-like dwellings that had symbolized north-south differences in Italy – marked a departure from neo-realism.

Watch this video on YouTube

Il Vangelo Secondo Matteo (The Gospel According to Matthew), filmed in 1964, dedicated to John Paul XXIII, the first pope to have opened up the discourse between Catholicism and Marxism.

A year earlier, Pasolini had received a four-month suspended prison sentence for “publicly undermining the religions of the state” for his short film La Ricotta, part of a neo-realist trilogy (RoGoPaG) which also included shorts from Godard and Rossellini. Now, The Gospel…, produced at a time when Pope John XXIII had initiated a communist-Christian dialogue at the Second Vatican Council in 1962, reflected Catholic as well as communist beliefs in its literate reading of Matthew. The film, in which Pasolini’s mother Susanna plays Mary and an unknown Spanish student Jesus, is an unequivocal condemnation of materialism and an attempt at a new spiritual reconciliation between Marxism and Catholicism.

Pasolini followed The Gospel… with Uccellacci e uccellini (Hawks and Sparrows, 1966), one of his most philosophical films which starred Toto the celebrated comic and Ninetto Davoli as father and son. They embark on a journey where they encounter a crow who attempts to enlighten them with stories from a Marxist position. It is a difficult task and the father and son, whose destination is never clear and who appear unaffected by either consumerism or idealism, eventually eat the crow as a mark of their indifference and security in their predicament.

Pasolini’s intention in Hawks and Sparrows was to articulate a critique of consumer capitalism and the vacuous pleasures it produced, while holding out the possibility of social justice and renewed political consciousness. His critique of bourgeois materialist values was further developed in films like Theorem (1968), and reached its pinnacle with Salo (1975).

By the mid-1960s, Pasolini was facing a breach with the left, despite maintaining much of his Marxism (he had been expelled from the PCI in 1949 following his dismissal as a teacher for alleged homosexual liaisons with his pupils in Friuli). His growing belief that the working class had become incorporated into consumer capitalism was followed by his controversial – and some would say simplistic – view that middle-class progressivism was dependent on superficial bourgeois decadence.

These differences became more overt and came to a head at the time of the May events in 1968. In the violent clashes that occurred at this time, Pasolini was very skeptical of the motives of the student movement, distrusting its class composition and perceived hedonism. He wrote a poem for L’Espresso which took the side of the police, whom he saw as poor southerners, sent to work for the state in order to escape the poverty of the south. He felt that the students should fight the legal and political system, not the sons of the poor. This brought him into major conflict with the left and he was physically attacked when speaking in Venice.

A Political Radical

Pasolini was now some way from the new left, which had put its faith in the politics of the new social movements. He opposed widespread drug use by the youth and students of this time, which he attributed to “middle-class unhappiness and refusal”. Drugs, he argued in a polemic with the leader of the Radical Party, Giacinto (Marco) Pannella, were merely a response to a loss of values and an attempt to fill a void leading young people into unhappiness, criminality or extremism. Rather than seeing it as a form of dissent, Pasolini saw drug-taking as a “surrogate for a specific elitist class culture”.

Moreover he maintained that drug-taking was indicative of a wider cultural malaise, which became one of the main themes dominating his final work. He condemned the “‘new economic power” which had led to the degradation of Italian cultural life. He saw through the paradoxes of the 1960s and 1970s, apparently offering new freedoms and sexual liberation yet containing in reality a “false” tolerance producing only cynicism and conformism.

These paradoxes were reflected in his own Trilogia della Vita (Trilogy of Life), a series of three films made in the early 1970s which captured the innocence of sexuality, but which he later renounced as no longer indicative of the world that now existed. Nor was he inspired by the growing medium of television. If drugs had elicited unhappiness, he found much TV “vulgar” and “degrading”.

He challenged the “false progressivism” and “false tolerance” advocated by mainstream political parties, including the Italian Communist Party, to which he continued to give qualified support. On the contrary, Italy was a “second-rate” power going nowhere. “In reality Italy is a horrible place”, he wrote in July 1975. “All one has to do is go abroad for a day and then return. The Italy of today has been destroyed exactly as was the Italy of 1945. Indeed the destruction is more serious, because we do not find ourselves among the ruins, however distressing, of houses and monuments, but among the ruins of values, humanistic values and what is more important popular values.”

Pasolini’s words in “The Ashes of Gramsci” are his own fitting epitaph:

“Between hope

and my old distrust I approach you,

chancing upon this thinned-out greenhouse, beforeyour tomb, before your spirit, still alive

down here among the free (or it’s

something else, perhaps more ecstatic, evenhumbler: an intoxicated, adolescent

symbiosis of sex and death….) And in this land where your passion neverrested, I feel how wrong

– here, among the quiet of these graves

and yet how right – in our unquiet

fate – you were, as you drafted your final

pages in the days of your murder.”

For Pasolini the main blame lay with Italy’s degenerate political class. The Christian Democrats (DC), which had ruled Italy virtually uninterrupted since the defeat of fascism, now assimilated the values of the capitalist revolution, despite the fact that its “hedonistic ideology” was some way from Catholic values. Yet as the remnants of the “clerico-fascism” of the post-war years adjusted to meet the demands of the “new economic power”, it only intensified the contradictions at the heart of the Italian state.

Watch this video on YouTube

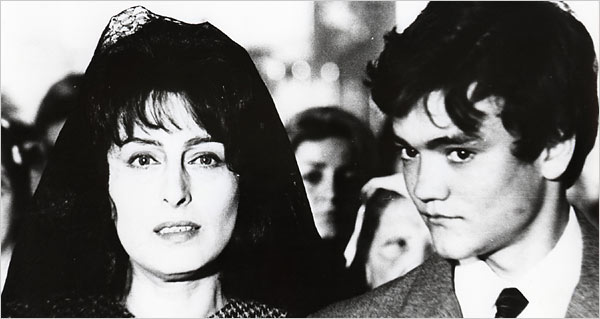

From Pasolini’s Mamma Roma, 1962, starring Anna Magnani.

For Pier Paolo Pasolini, Italy in the 1970s was not a normal country, but one run by a parliamentary regime, corrupt to the core, complicit in Mafia dealings, and above all conspiratorial in sustaining its own grip on power. It was “a ridiculous and sinister country.” The spate of neo-fascist bombings which had gone unpunished and the so-called “strategy of tension,” in which fear of a communist takeover was triggered by violent terrorism, continued to prevent any kind of political and social change.

This was despite the considerable efforts of the communist party. A surge in the PCI’s support in the mid-1970s had been followed by a controversial “historic compromise” with the DC as a way of asserting greater influence. Pasolini, like many others on the left, was unconvinced by this strategy, though he also rejected the drift to violence of some of the left groups. He thought the communists were in danger of being submerged into the trappings of power, notably through their pragmatic negotiations with the DC and faith in the state as a repressive instrument.

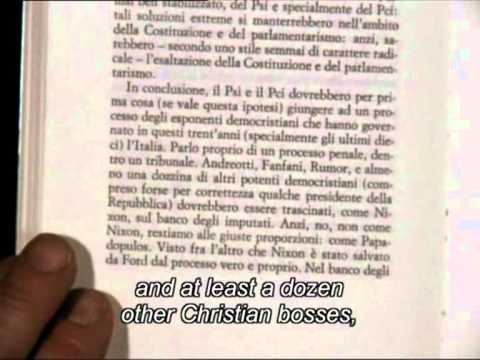

In an extraordinary series of articles in Corriere della Sera and Il Mondo in August-September 1975, Pasolini argued for the Christian Democrat leaders (including Giulio Andreotti and others) to be put on trial. The only way to remove these leaders from their centres of power (what Pasolini called the “palace”), was a full criminal trial. The DC was guilty of a series of crimes, he argued – including complicity with the Mafia in government decision-making; covering up the neo-fascist bombings in Milan, Brescia and Bologna between 1969-1974; misuse of public funds; collaboration with the CIA; and conspiring with the military and CIA to halt the rise of the left.

“Over the whole of Italy’s democratic life,” he wrote, “there looms the suspicion of Mafia-like complicity on the one hand and ignorance on the other; from this is born almost of its own accord a natural pact with power – a tacit diplomacy of silence.”

His warnings were accompanied by an appeal to citizens, intellectuals and movements to demand the truth from Italy’s rulers: “Until they know all these things…the political consciousness of the Italians will be incapable of producing a new awareness. That is to say Italy will be ungovernable.”

“Why the Trial?” appeared in Corriere della Sera on 28 September 1975. Just over a month later Pasolini was murdered. A lot of people had motives: leading Christian Democrats who, three years later, sat by and watched ex-prime minister Aldo Moro die at the hands of the Red Brigades, after he too denounced them as people who “lived for and by power”; Mafia bosses with direct access to the centre of power in Rome; the neo-fascists of the MSI, the heir to Mussolini’s Fascist party. Pasolini had repeatedly denounced the perceived cover-ups that followed fascist bombing campaigns, and his last film Salo had satirised Mussolini’s fascist regime.

More evidence may shed light on these and other events. However, many of Pasolini’s friends fear that the real truth will never come out, reminding us that at the time of the original trial Italians wanted a quick judgment. The implicit assumption of much of the media was that the life of a homosexual and troublesome intellectual was bound to end in such circumstances.

For the full article, please see: Open Democracy

Geoff Andrews is the author of Not a Normal Country: Italy After Berlusconi (Pluto, 2005)

Updated 26 December 2020

Pingback: Vittorio De Sica: The Alienated Unemployed in "Bicycle Thieves" | WilderUtopia.com

Pingback: Orson Welles: Tragic Hero, Sacred Monster, Profane Clown | WilderUtopia.com

Pingback: Ongoing Reconsideration of Pier Paolo Pasolini | WilderUtopia.com

Pingback: Griechisches Feuer Maria Callas Und Aristoteles Onassis - Wiring Diagram

Pingback: Federico Fellini Movies: Intuitive Visual Art - WilderUtopia