The Wall Street Journal praised SASOL’s move to industrialize the Lousiana Bayou with fracked natural gas. But the proposed project by the apartheid-supporting state oil company from South Africa, using Nazi technology, may spell the end for a 224-year-old community founded by freed slaves.

As Fracking Keeps Pumping, A Qatar Grows on the Bayou

By Dennis Berman, Published in the Wall Street Journal

It’s the tale of a company called Sasol, the former South African state oil company, which is embarking on what could be the single-largest foreign investment project in U.S. history. Sasol is building a 3,034-acre energy complex near a bayou in Lake Charles, La. Tapping into cheap, fracked natural gas as well as the pipeline and shipping infrastructure along the Gulf Coast, Sasol plans to spend as much as $21 billion there.

It is expensive, elaborate and dirty work. Sasol plans to reduce, or “crack,” the gas into ethylene, a raw chemical used in plastics, paints and food packaging. It also plans to convert the gas into high-quality diesel and other fuels, using a process once advanced by Nazi scientists to power Panzer tanks. The state of Louisiana is even kicking in $2 billion of incentives to make it happen.

The South African energy and chemical producing company, Sasol emits far more greenhouse gases than any of the top 100 companies listed on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange, the Sunday Times reported.

This is engineering on a scale so large that it requires closing 26 public roads, buying out 883 public-property lots, and hiring 7,000 workers at peak construction. Some 100 additional trucks will be on the road each day once the complex is completed. Entrepreneurs have already begun construction of a “man camp” to house 4,000 temporary workers streaming into Lake Charles for this and other projects.

STORY: Beasts of the Southern Wild: Bayou Culture Sinking into the Gulf

Gas Boom in the US Underestimated — Or Just More Really Hot Air

In that way, Sasol is a metaphor for what we don’t yet understand about America’s gas boom. Most know what fracking has meant for oil and gas prices. But because much of the work hasn’t started yet, few appreciate the true extent of the industrialization that’s about to begin.

So let’s put it this way: We are building a Qatar on the Bayou. From whole cloth, companies are laying new cities of fertilizer plants, boron manufacturers, methanol terminals, polymer plants, ammonia factories and paper-finishing facilities. In computer renderings, the Sasol site looks like a fearsome, steel-fitted Angkor Wat.

The predominantly African-American community of Mossville, Louisiana may cease to exist as South African chemical giant Sasol paves the way for a massive new plant by paying for residents to relocate. — AlJazeera America

Comments from the Lousiana Environmental Action Network

In all, some 66 industrial projects—worth some $90 billion—will be breaking ground over the next five years in Louisiana, according to the Greater Baton Rouge Industry Alliance. Tens of billions of other new investments could be coming, says Louisiana’s economic development secretary, Stephen Moret. How many projects will actually get built remains to be seen.

Assuming that most will, you realize we are still probably underestimating the positive impact of the gas boom on both local and national economies. The entire GDP of the state of Louisiana is about $250 billion annually.

“As an economist, I can only say, ‘Wow. Holy Cow,'” said Loren Scott, a Louisiana economist who has studied the state for 40 years. “We typically measured expansion in terms of hundreds of millions of dollars. Something like that makes your eyes bug out.” He expects, for instance, that once 10-year tax-abatement deals expire, schools boards will “find themselves with a bonanza.”

An analysis conducted by the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) in February determined that the new project “will result in significant net emissions increases” of greenhouse gases, promethium, sulfur oxide, nitric oxide, and carbon monoxide. By its calculations, the plant will spew out more than 10 million cubic tons of greenhouse gases per year. (By contrast, the Exxon-Mobil refinery outside Baton Rouge, a sprawling complex that’s 250 times the size of the New Orleans Superdome, emits 6.6 million tons.) Yet the same agency ruled “no significant impact” on air, water and soil. — Tim Murphy in Mother Jones

Similarly, we probably underestimate the deepening shortage of skilled laborers needed to design, weld and operate these mechanical beasts. Wages are already pushing higher, which could delay or even squelch some projects.

An Environmental Disaster… With “No Impact” on the Air, Water, and Soil?

So, too, do we not understand the environmental effects of this building binge. The Sasol plant alone is expected to emit 85 times the state’s “threshold” rate of benzene each year. It will also produce massive streams of carbon dioxide and treated water. And it is just one new facility of many. “I don’t want to wear a gas mask to go to bed at night if this plant is coming in,” said Rufus Victorian, a pipe fitter, at a 4½-hour public hearing on the plant in March.

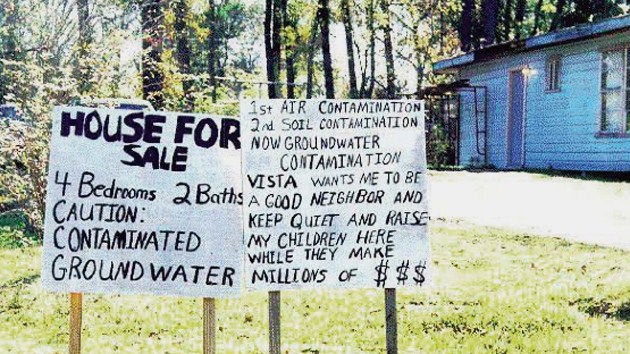

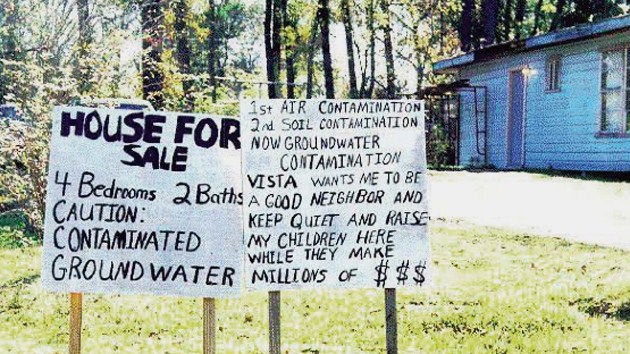

Mossville residents have fought for their environmental rights for decades. Chemical contamination of the Mossville area in the 1990’s spurred legal action and some home buyouts. A company called Condea Vista was found guilty of “wanton and reckless disregard of public safety” for a 1997 spill that contaminated Mossville’s local estuary. Sasol acquired Condea Vista in 2001.

Amid the coming boom, Sasol’s vision is especially audacious. The history of gas-to-liquid plants is mixed, prone to cost overruns and technology snafus. Should gas prices rise, or oil prices fall, they can quickly become huge money losers. Right now, the arbitrage is in Sasol’s favor. Oil trades at around 24 times the price of natural gas. In 2007, by comparison, it was around seven times. Sasol needs the ratio to be at least 16 to make money.

Historically, Sasol did a lot of its work converting coal to fuel, a necessity during the apartheid era in South Africa when oil supplies were constrained by a trade embargo. The company still carries an outsider’s edge, going wherever the best deals may be. That has taken it to Qatar, as well as Iran, Uzbekistan and Nigeria.

Monique Harden, co-director and attorney for Advocates for Environmental Human Rights, shared the following statement with The Stream on March 27: “As a company established to support the apartheid regime in South Africa, Sasol should know by now the power of people to overcome injustice. We are standing with the residents of Mossville, Louisiana in defense of their human rights.” — AlJazeera

U.S. sanctions forced Sasol to leave Iran, where it purchased crude oil for a South African refinery and invested in a chemical venture with a state-backed company. Iranian imams do not make the best bedfellows—which is partly why Sasol Chief Executive David Constable appreciates doing business in America. “If you’re going to build a plant, from a logistics standpoint?it is No. 1 in the world,” said Mr. Constable in an interview. Access to cheap gas, customers, capital, rule of law and ease of building “ticks all the boxes very nicely. It couldn’t have happened to a better country.”

Louisiana’s waterways are a huge plus, making it easy for Sasol to ship its products via barge. They also make it easier to deliver the four 2,000-ton chemical reactors needed for the plants. The docks are just 1½ miles from the Sasol site. Then there are the gas pipelines, which make it easy to pull in gas from the shale fields of Texas.

“That’s why it’s so much more difficult for a China or Europe to jump into shale gas in a big way. If you look at the natural-gas pipelines around the country, it’s like a spider web,” Mr. Constable said.

There’s much more toil for both Sasol and the country at large. The environmental costs cannot be overlooked. But in the grand veneers of politics, there is much to work with here. You can almost hear President Obama announcing his begrudging approval of the controversial Keystone XL pipeline with a line that goes something like this: “Friends, we are taking dollars out of Iran’s pockets and putting them into our own. The energy century is going to reindustrialize America, and if we do it right, this is going to be bigger than we even know.”

—Email dennis.berman@wsj.com

Twitter: @dkberman

http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB20001424052702304811904579587673420436230

Updated 28 July 2018

Absolutely disastrous! How can we help stop this?

Excellent question, Violeta. The project is under review right now, with little to stop the “authorities” in the state of Louisiana from approving the project. I will delve a little deeper…

Pingback: Fracking: Civil Rights Hero Takes on Big Oil | WilderUtopia.com